Throughout his early boyhood in Dunbar, Scotland, where he was born in 1838, John Muir felt the influence of two opposing forces: his urge to explore the natural world, and the domineering father he faced at home. To spend his days scouring the fields for skylarks or splashing in the tide pools beside the North Sea was to risk paternal lashings in the evenings.

Nature tended to win. Muir’s own wildness, he recalled decades later in The Story of My Boyhood and Youth, was “as invincible and unstoppable as stars.”

Today, over a century after his death, Muir is revered as the founder of the Sierra Club and a driving force behind the creation of U.S. national parks. He is regarded as the father of the conservation movement, and his name graces a bucket list of landmarks: glaciers, museums, parks, an extraordinary 211-mile segment of the Pacific Crest Trail, and a 134-mile path across his native Scotland christened John Muir Way in 2014.

In the West, where he left his deepest imprints, Muir is an icon. But like the peaks of Yosemite National Park that so inspired him, his image often appears at a misty distance. Only rarely do we ask how Muir the adventurer evolved into an activist, or what compelled a man so fond of roaming to stop and stand his ground.

“There’s a long explanation, much of it conjecture,” says Will Collin, a trustee of John Muir's Birthplace interpretive center in Dunbar. “But the short answer is, it was in his blood.

In 1849, Muir’s father, Daniel, moved his family to Wisconsin in pursuit of a stricter form of Protestant faith. Like Daniel, young John was stubborn and rebellious, enduring the hardships of pioneer farming and his father’s intense work ethic. He resisted Daniel’s mandate that he read no books other than the Bible. Ultimately—and significantly—he rejected his father’s fire-and-brimstone outlook. In nature, Muir believed, lay the divine.

Despite having little formal schooling, Muir enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, where he excelled at mechanical engineering and displayed a genius for whimsical inventions, including an “early-rising machine,” which automatically tilted a bed upright to roust sleepers onto their feet. College also exposed him to theories of glaciation that would later inform his views on the forces that shaped California’s Yosemite Valley.

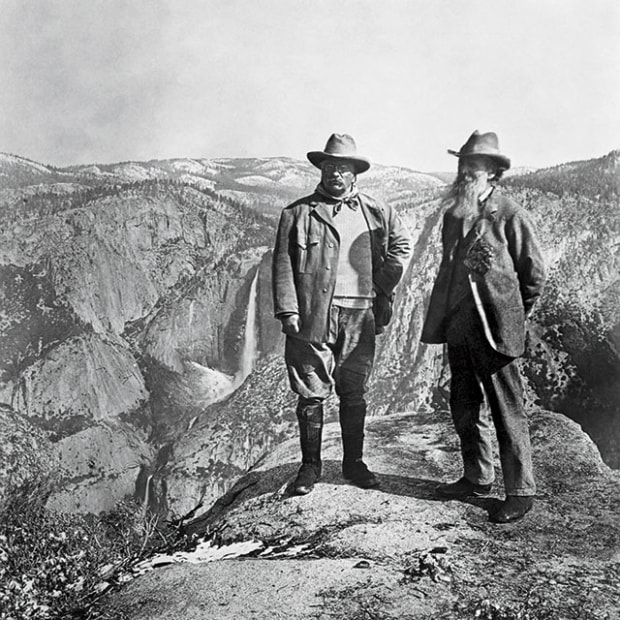

Conservation was the topic when John Muir took Theodore Roosevelt to Yosemite in 1903.

But nothing influenced Muir more than the call of the wild. It grew more urgent after graduation, when a factory accident left him blinded for several weeks. His first anguished thought, he noted later, was that “I should never look at a flower again.”

The experience propelled Muir to undertake a 1,000-mile walk toward the Gulf of Mexico, pursuing what he described as the “wildest, leafiest, and least trodden way I could find.” He also visited Cuba and crossed the Isthmus of Panama. In 1868, he sailed up to San Francisco and set out on foot to see the Sierra Nevada and its grand cathedral, Yosemite Valley. The first time he gazed across California’s San Joaquin Valley toward the Sierra, he wrote that the towering peaks “seemed not clothed with light but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city.”

He had intended to linger nine months in those “divinely beautiful” mountains, but he wound up spending his remaining years exploring them, in person and in print. Alongside splendor, Muir found despoliation: logging, mining, overgrazing. It outraged him. “He had no patience for stupidity,” says Steve Holmes, author of The Young John Muir: An Environmental Biography. “And so much of what people were doing seemed to him exactly that.” Defacing the wilderness struck Muir as not merely senseless but sacrilegious, and he rose to nature’s defense with spiritual fervor.

Muir’s lyrical writing lent environmentalism a unique eloquence. His articles, published in influential outlets such as the New York Tribune and the Atlantic Monthly, earned him the respect of leading thinkers and the ear of U.S. presidents.

In 1880, life interrupted. Muir married Louie Wanda Strentzel and settled in Martinez, California, to help run her family’s orchards. During his 10 years in charge, Muir proved an efficient manager, boosting profits and arranging for the construction of a local rail terminal for shipping fruit. Farm work was exhausting, but it gave Muir the financial freedom to continue writing. In a series of articles penned in 1889, he championed creating a national preserve around Yosemite. The following year, an act of Congress did just that.

Muir was far from done. In 1892, he helped found the Sierra Club, whose mission, Muir said, was to “do something for wildness and make the mountains glad.” He served as the club’s president until his death.

Muir’s final campaign was waged on behalf of Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite, and it ended in defeat in 1913 with federal approval to build a dam that transformed the valley into a reservoir, the prime source of San Francisco’s water supply. He died of pneumonia a year later, and some accounts depicted him as broken by the loss. But if he was bitter, he didn’t show it.

His legacy is marked instead by battles won. Though his full impact is impossible to measure, its vastness is suggested by the great yawn of the Grand Canyon, the fjords of Glacier Bay in Alaska, and the prehistoric majesty of California’s Sequoia National Park. These wild places endure thanks to the wildness of the man himself.